When gathering information, ask more open questions (who, whose, what, when, which, why, and how). They will be perceived as less threating and more collaborative while getting you more helpful information.

By Marianne Eby

You are about to begin a difficult project at work in conjunction with your co-worker, and he asks, "Want to grab a cup of coffee before we get started?" You may not want coffee, you may be busy, you may be dreading working with this person, or you may think chit chat is a waste of time. But if you are going to successfully complete this project, you would be wise to respond with a resounding "Yes!" You have just received an "emotional bid" that holds the key to you getting more of what you want in the many negotiations that will unfold during this project.

As John Gottman described a decade ago in his book, The Relationship Cure, an emotional bid is a question, gesture, or expression that implies, “I want to connect with you.” The label "Emotional bids" may be 21st century nomenclature, but the idea is as old as the first negotiation between cave men setting out on a hunt who sharpen sticks together, and will later have to negotiate who gets the best meat of the kill.

Emotional bids are part of all developing relationships, including those between co-workers and negotiating counterparts. If your polite answer to such a bid is "sorry I don't drink coffee" or "thanks but I have too much work right now," you are missing an critical opportunity to connect in a way that supports your inevitable ask for something you want.

Many of us fail to recognize or extend emotional bids. As a good negotiator, you already know that relationships are critical in your negotiations -- with customers you can't afford to lose, suppliers you need, and partners you want. The relationship you develop with the other party, whether positive or negative, impacts every aspect of your negotiation. Yet we spend more time alone completing tasks, and avoiding interaction, only to lament, "We don't have a trusting relationship!"

Recognize emotional bids for what they are -- a prime opportunity to build affiliations, find common ground or interests, and understand each other outside the conflict zone.

Be on the lookout for "emotional bids" and use them yourself. An "emotional bid" can be an interesting "tweet" or funny story, sharing an industry related article, a recommendation for a good book or restaurant, and a million other ways to connect.

Remember, institutions don't negotiate. People do. And people give the best deals to people they connect with -- people they like.

By Marianne Eby

Even when you prepare extensively for face-to-face negotiations, you often feel like you are on stage. Everyone is watching to see if your reaction or next move will ensure progress, or prevent it. Sometimes everything goes according to your intended script, and what you practiced must now come off as an unrehearsed reaction. Other times you have to respond to unexpected turns in the conversation. To get better at both these negotiation skills, let’s take a few lessons from Improv.

I was a theatre major in college in the '80s, and often draw on the Improvisation skills I learned in those acting classes and later as an attorney to help me now in my face-to-face negotiations. You can do it too.

What is improvisation? Without getting technical, it’s using words or actions in response to a stimulus in your environment, such as a question, an inner feeling, or some one else’s reaction. It involves spontaneity. Common terms for improvise are ad lib, extemporize, off the cuff, and play it by ear.

Theatre actors practice Improvisation as a way to find the spontaneity that the audience will need to experience when the actors deliver a script for the hundredth time. Improvisation teaches actors how to listen, sense others around them, communicate clearly, trust their instincts, and appear both spontaneous and confident in their reactions and choices. These same skills are critical to negotiating.

Improv Skills in Negotiations

Foremost among Improvisation skills are listening actively and building on that information. In Improv we use a simple "yes and" statement where the actors affirm what their partner has said and then add information. To do this well requires listening to a partner, internalizing what they have said, and coming up with a statement that moves the relationship between the actors forward.

It’s the same in negotiations. If you find yourself rehearsing your response while your counterpart is talking, you are not listening, and it will be obvious when you respond about your needs rather than theirs. To practice listening, use this simple Improv exercise in response to your counterpart. Say “Yes, and....” Knowing that you are going to say, “Yes,” your mind will easily focus on what is being said to you so that you don’t mistakenly concede something. Focusing, in turn, will allow you to be responsive in a way that your counterpart feels heard.

Actually saying "Yes" in negotiations can have dreadful ramifications, so in negotiations we want to be a bit more verbose. Try saying "Yes I see what you mean, and...; Yes, I am beginning to understand, and...; Yes you have some valid points, and...." You get the idea.

In Improv, like negotiations, the goal is to move the conversation forward in a way that makes sense for all actors. In Improv, one actor makes an offer -- to sit down at an imaginary table, to go inside a door, to talk about his female tennis coach – and another actor is supposed to accept the offer in a way that takes the scene forward. The responding actor can’t walk through the imaginary table, or talk about his mate’s male tennis coach for example. To do so is called "blocking," and it prevents the scene from developing.

It’s similar in negotiations. When one party makes a demand or proposal, it provides an opportunity to move forward -- closer to agreement. That doesn’t mean you have to accept the offer; it means you have to talk about it. And to talk about it, you have to listen. At a minimum, listening can be a powerful concession to other party’s need to be heard. Listening also enables you to understand the perceptions, emotions, and underlying messages of the other party, while building rapport, trust, and a strong alliance with the speaker. When you say "Yes, and...," ask questions, seek clarification, and suggest nuances that might work, you have demonstrated that you listened, and the conversation has moved forward. Don’t be a blocker, be an improviser!

The next time you engage in negotiations consider taking a lesson out of the Improv playbook, and use some “Yes and” statements. Say ‘yes’ by validating the information that the other party has given you, ‘and’ then add some information to demonstrate that you understand their position on the matter. See how the scene plays out!

By Marianne Eby

Taking gender into consideration as one factor that may affect a person’s receptiveness to an offer is helpful, as long as you remember that broad categories don’t always work and many other factors affect a negotiator’s style besides gender. But yes, it may help to present your offer differently to a man than to a woman.

This question came up at one of our negotiation workshops recently, during a discussion about how different communication styles affect negotiations. A participant brought up a rule of thumb she’d read about gender considerations when asking for something:

If you’re asking something from a woman, start with small talk or a narrative that prepares her for your request. But if you’re asking a man, do the opposite – open with your request, and elaborate with context and detail afterwards.

Was this a good rule of thumb, and if so would it be useful in negotiation?

Let’s consider this rule in a simple negotiation. If you want to ask your neighbor to remove a tree that leans into your yard, and your neighbor is a woman, you would begin by talking about her garden, your garden, and what is thriving in your yards, before asking about the tree. If your neighbor is a man, on the other hand, such a rule of thumb suggests you start right off with the “ask” about the tree, and fill in the details next.

The participant was spot on. In fact, the last few years of research on the differences between male and female brains can help us. In the 2008 book Leadership and the Sexes: Using Gender to Create Success in Business, Barbara Annis and Michael Gurian describe the differences in male and female brains (there are over 100, and how understanding them can make or break effective communication in corporate culture).

The research tells us that as it turns out, many clichés about gender -- i.e., women are more emotional, men are less talkative -- are proven by PET and SPECT scans of our brains! Images of brain activity show that:

These differences have contributed to the different expectations women and men bring to communication, and to the clichés or cultural norms that have developed.

It’s easy to dismiss the chit-chat part of the approach to a woman as a waste of time. But it’s actually quite efficient, because women tend to get lots of clues during the chit chat. It’s not that the chit chat itself is so stimulating to them; what is stimulating is the wealth of information they gather from the chit chat about trust, comfort/discomfort, readiness to close, ect.

Men, on the other hand, tend to get fewer or no clues during such chit chat, so it makes sense that men find it stressful or wasteful: they find themselves processing what seems to be otherwise useless information.

Let’s say we approach Bob and say: "Hi Bob, how’s it going? I’ve got a question about this tree of yours that is causing me some concern.” For Bob, it is important to have a kind of frame or subject heading for the conversation before he can engage productively. Without that, the extra effort to establish “relational harmony” may be more verbiage and more detail than he wants to absorb at that moment. The chit chat would be inefficient and ineffective.

Let’s say we approach Sally and say: "Hi Sally, how’s it going? You really did get a nice deep blue in that hydrangea. How did you do it?....Your tulips were magnificent this year as well. Any tips for me?.....Now tell me about this tree….” For Sally, the entry dialogue is important: it establishes that they are friendly neighbors, with an interest in a win-win solution, which is her “frame” for a problem-solving negotiation about the tree.

Do these findings about the male and female brains change the way we negotiate in business? No and Yes.

No -- Establishing rapport and trust are critical parts of any negotiation, whether your counterpart is the same gender or not. And that rapport typically depends on a conversation which helps uncover shared interests.

And Yes – Style matters, and a master negotiator adopts strategies that will be most effective with the style of his/her counterpart. Establishing rapport is critical, but it doesn’t have to be the opener.

The real value of our workshop participant’s rule of thumb is that it gives us one simple tip to take with us on the road: plan your approach; sequence and timing matter.

By Thomas Wood

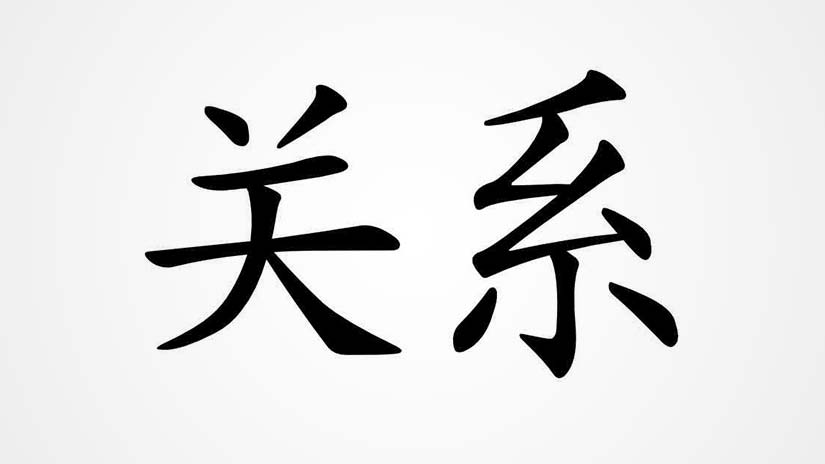

My colleague blogged about Guanxi last month, the age-old concept that we teach in our Best Negotiating Practices workshops. Her post on Guanxi (Get in Touch with Your Guanxi) reminds me of the man who turned Guanxi into a mathematical formula.

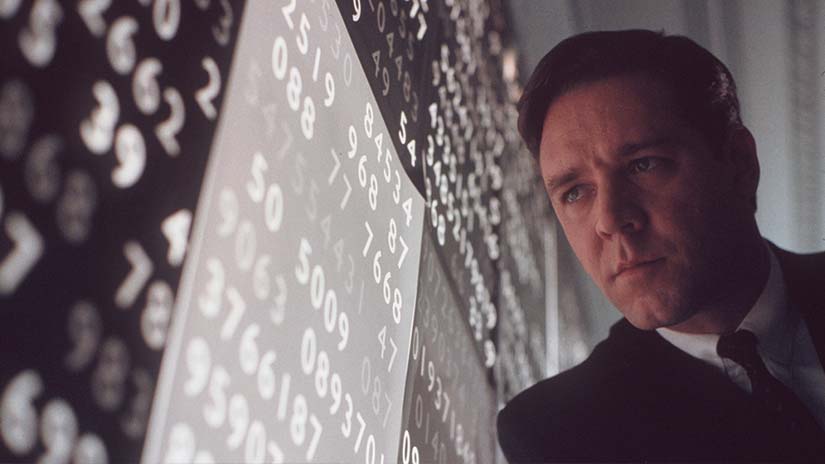

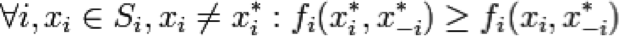

In the 1950s, John Nash took the idea of Guanxi -- that caring about the relationship is as important as the outcome -- and applied it mathematically. Years later Nash won a Nobel Prize for his work. Nash suffered from acute chronic schizophrenia most of his career, and as a young prodigy was obsessed with coming up with an original idea. But did he?

Up until this point, most negotiations in the West were focused on the deal – the outcome – the conditions. What did John Nash introduce as an “original” idea? Relationships matter.

Are relationships new to win-win? No! Ancient cultures have valued relationships for thousands of years. John Nash borrowed the concept of Guanxi to support his theory. What is new is that John Nash and his colleagues proved that a win-win result is predictable and repeatable.

John Nash demonstrated that the then predominant theory of economics – Adam Smith’s premise that individual ambition serves the common good and that the best result comes from everyone doing what’s best for himself – was not complete. Nash showed that the best result comes from everyone in the group doing what is best for himself AND the group. You have to factor in all the relationships and connections – you and your stakeholders, they and their stakeholders. You also have to understand what people need with regard to both ego and outcome. You can get the full effect of Nash's theory from the acclaimed 2001 movie A Beautiful Mind.

When you take these factors into account, you reach a result that benefits all – that’s win-win. And how do you get there? With collaborative interest based negotiation strategies, starting with a healthy dose of Guanxi. Some in the West call this the birth of win-win, because it set us on a new course of negotiation mastery and success, as well as paved the way for successful negotiations with cultures more astute at negotiating.

By Marianne Eby

Our clients do extensive business in China, where negotiations tend to be a long involved process. What you thought would be a simple business negotiation often turns into multi-day affairs with many delicious meals, multiple toasts, and tours around the factory. While it takes time, this focus on Guanxi, which roughly translates to “relationships and connections,” is viewed as both effective and efficient in China. Good negotiators everywhere would do well to take a lesson and get in touch with their Guanxi.

The Chinese view their business relationships as cooperation amongst various parties that support each other towards mutual gain, where “business favors” or concessions are readily and voluntarily given, knowing that business partners would also be ready to give. Guanxi is a complex concept that involves respect, reciprocity, and a certain deference to the person with more authority, all in an effort to achieve a mutually beneficial relationship.

One famous story of Chinese relationship building is the story of Microsoft’s growth in China. Urban legend had it that on his first trip to China in the mid 1990s, Bill Gates insulted the Chinese President Jiang Zemin by wearing jeans and only leaving time for a brief visit. The legend had China’s President stating that Mr. Gates would be wise to learn more about Chinese culture, essentially saying that understanding China’s customs would pave the way for better working relationships in the country. This legend of course turned out to be pure myth and was later debunked in the 2006 book, Guanxi (The Art of Relationships): Microsoft, China, and Bill Gates’ Plan to Win the Road Ahead by Robert Buderi and Gregory T. Huang, which explored the success of Microsoft’s software laboratory in Beijing, China. The real story is that Gates and one of his key visionaries, Nathan Myhrvold, executed a strategy that set the company and the country on a long term course to build a mutually beneficial relationship by harnessing the talent from within China and learning the cultural knowledge necessary to be successful.

According to Buderi and Huang in Guanxi and the Art of Business, “So far, the company has invested well over $100 million and hired more than 400 of China’s best and brightest to turn the outpost into an important window on the future of computing and a training ground to uplift the state of Chinese computer science – creating dramatic payoffs for both Microsoft and its host country….” China is reaping the benefit of an elite corps of computer scientists, while Microsoft’s barriers to entry were eased.

The legend, the truth, and also the ultimate success of Microsoft in China demonstrate an important lesson: doing business requires understanding the culture of your counterparts and making an effort to build relationships in the ways that are important to them.

Negotiations in western cultures proceed at a speedy clip more often than not, but relative to the speed and cultural nuances, there is always a need to invest in the relationship. Building a strong connection up front with your supplier, customer or partners provides an invaluable foundation of trust and connection that supports all future negotiations in the relationship. Get in touch with your Guanxi!

By Thomas Wood

What if someone you are dealing with seems unable or unwilling to negotiate? You sense that, for personal or cultural reasons, or because of inexperience, they don’t warm to, or recognize, your attempts to open negotiations. Do you give up?

This was the question that came over our Need Help Now web advice service, in which one of our workshop participants was was dealing with a new buyer at a key customer. Often we see a disinclination to negotiate from very smart technical people, such as scientists, technologists (techies, IT, programmers), and engineers. We also see it in the helping professions (researchers, nurses, doctors, laboratory technologists). It applies equally to someone who has resources you need, or authority to give you something you want (a promotion, a better assignment, an extension on a deadline). Your assessment of the “negotiation environment” tells you that despite your counterpart’s inexperience or unwillingness when it comes to negotiating, a collaborative negotiation would indeed yield a great outcome for both sides.

Let’s start with the absolute DON’Ts:

1. Don’t ask them to ‘negotiate’ with you. Such an approach runs the risk of raising red flags and making them nervous. If they feel intimidated, they will avoid further conversation. If they believe negotiating is akin to arguing or win/lose and they are conflict averse, they will either retreat or take a hardball stance.

2. Don’t make any offers (demands, proposals) until they do.

So what do you do?

When dealing with a novice or non-negotiator, try to transform the interaction into one where the other party feels like they are simply having a conversation. Remember, collaborative negotiation is at its heart a conversation, only with a goal of expanding value.

How to begin?

Model the characteristics of a collaborative negotiator:

The idea is to uncover their interests and fears, to gain their trust, and help them see how you can arrive at a “win-win” solution. If you do that, you may find yourself developing a joint agenda and moving into bargaining without your uneasy counterpart ever realizing they are negotiating.

By Thomas Wood

When you disclose valuable information to your negotiation counterpart, you want equally valuable information in return. Right? Not always. Sometimes what you seek in return is a new level of trust – that will lead to getting more information and ultimately, trades that create value. Sometimes "one-way" is "two-ways".

Please provide us with some details and we will be in touch soon!